- WILLKOMMEN

- DISCOVER GERMANY

- GEOGRAPHY OF GERMANY

- HISTORY OF GERMANY

- Timeline of German History

- The Hanseatic League

- The German Confederation

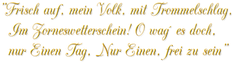

- The Hambach Festival

- The German Revolution of 1848/49

- The North German Confederation

- The German Empire

- Otto von Bismarck

- German Colonies

- World War 1

- The Weimar Republic

- National Socialism

- World War 2

- Zero Hour

- West Germany

- German Democratic Republic

- German Reunification

- LAND AND PEOPLE

- GERMANY'S SYMBOLS AND SLOGANS

- GERMAN CITIES

- CLIMATE OF GERMANY

- VEGETATION AND WILDLIFE

- SPORTS IN GERMANY

- POLITICAL SYSTEM

- GERMAN LITERATURE

- GERMAN MUSIC

- ENTDECKE DIE USA

- GEOGRAPHIE DER USA

- GESCHICHTE DER USA

- Chronologischer Abriss der Amerikanischen Geschichte

- Die 13 Kolonien

- Die Amerikanische Revolution (1775-83)

- Die Junge Republik

- Krieg von 1812

- Amerikanisch-Tripolitanischer Krieg

- Lewis und Clark Expedition

- Westexpansion

- Monroe Doktrin (1823)

- Mexikanisch-Amerikanischer Krieg

- Transkontinentale Eisenbahn

- Der Amerikanische Bürgerkrieg

- Die Rekonstruktion der Republik

- Spanisch-Amerikanischer Krieg (1898)

- Die USA im I.Weltkrieg

- Great Depression

- Die USA im II.Weltkrieg

- 11. September

- Geschichte der Bürgerrechte

- LAND UND LEUTE

- SYMBOLE UND SLOGANS DER USA

- STÄDTE DER USA

- KLIMA DER USA

- SPORT IN DEN USA

- FLORA&FAUNA

- POLITISCHES SYSTEM

- LITERATUR DER USA

- Epochen der amerikanischen Literatur

- Kurzportraits

- William Bradford

- James Fenimore Cooper

- Frederick Douglass

- Ralph Waldo Emerson

- William Faulkner

- Francis Scott Fitzgerald

- Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Ernest Hemingway

- Washington Irving

- Emma Lazarus

- Herman Melville

- Edgar Allan Poe

- John Steinbeck

- Henry David Thoreau

- Mark Twain

- Booker T. Washington

- Walt Whitman

- John Winthrop

- US-MUSIK

- GUIDE

|

OVERVIEW

|

THE DESIRE FOR GREATER CIVIL RIGHTS

The German Revolution of 1848/49 was a series of political and social upheavals that occurred throughout the German states. The revolution was sparked by the demand for constitutional reform and the desire for greater democracy and civil rights. The revolutionaries sought to create a united German nation-state and end the fragmentation of Germany into numerous small states. The revolution was initially successful in many parts of Germany, with constitutional assemblies established and liberal reforms enacted. However, the revolution ultimately failed to achieve its goals, as conservative forces reasserted their control and suppressed the revolutionary movements. Many political heads fled to the United States and became known as the 48ers. The revolution did, however, set the stage for further attempts at German unification and laid the groundwork for the eventual creation of a unified German state in 1871.

EARLY FORMATIONS

In 1848, news spread throughout the German Confederation that an insurrection had overthrown the French King Louis-Philippe. As a result, sympathetic but loosely coordinated protests broke out in the German states, as well as many other European countries. Since the War of Liberation, student unions or Burschenschaften had been promoting the idea of a unified, democratic Germany under the colors of black, red, and gold. Their ideas were expressed when a large group of people peacefully gathered at Hambach Castle in 1832. However, other groups attempted to achieve German unification through more violent means. In 1833, for instance, the Frankfurt guardhouse was stormed, and police officers came under attack. The attackers planned to storm the parliament the following day to trigger a coup d'état. The Hambach Festival of 1832 laid the groundwork for growing unrest in the face of political censorship. The rebellions of 1848 demonstrated widespread discontent with the traditional autocratic political structure of the Confederation. Moreover, the hard times of the late 1840s, caused by economic depression, transformed these rebellions into a full-blown revolution.

Whereas artisans in big cities were fighting for a stable livelihood, the middle-class was committed to liberal

principles. In March 1848, crowds of people gathered in Berlin to present their demands for liberal reforms in an address to the king. On March 18, fierce fights swept across Berlins streets, and

more than 200 civilians lost their lives. King Friedrich Wilhelm IV yielded to all the requests, which included:

- parliamentary elections

- a unified Germany with a constitution

- freedom of the press and

- freedom of assembly

The German Revolution is also called the March Revolution.

THE FORTY-EIGHTERS

The German Revolution of 1848/49 had historic relevance in the United States, which welcomed thousands of German refugees seeking political freedom. However, the German aristocracy was able to defeat the democratic process in 1849 by dividing the middle and working classes. As a result, many liberals were forced into exile to escape persecution, and those who fled to the United States became known as the Forty-Eighters.

Immigration to the US had already increased since 1845, but it spiked after the failed revolution of 1848. It is important to note that only the intellectuals and leading political heads who immigrated to the United States are called 48ers (not to be confused with the 49ers who moved to the West due to the California Gold Rush). Approximately 4,000 immigrants fell into this category. Although these refugees did not receive any governmental support, most Americans sympathized with them because of their shared democratic ideals.

The Forty-Eighters founded German-American organizations such as Turnvereine and became known as the Turners, who stood for liberty and supported the new Republican Party. Many of them were able to put their democratic ideas into action on American soil. Not a few 48ers became Americanized and launched successful careers, such as Carl Schurz, who became an ambassador to Spain and a general in the American Civil War before serving as Interior Secretary. Another German-American who made his career in the United States was Franz Sigel, who had led a militia during the Baden insurrection before fighting as a general for the Union cause during the American Civil War (1861 - 1865).

BROKEN DREAMS

However, there were some 48ers who still engaged for the German cause once they reached American soil. They experienced rejection because they were expected to assimilate to American customs and practices. Some of them went back to Germany with broken dreams when things calmed down.